The Final Frontier: navigating the booming Space Economy (expected to reach $1.8 trillion by 2035)

From science fiction to reality, the final frontier is now open for business. As we stand on the brink of a new era in human history, the space economy is no longer a distant dream but a tangible, rapidly expanding market. This article delves into the intricate web of innovation, challenges, and opportunities that define our journey beyond Earth’s atmosphere. Buckle up as we explore how entrepreneurs, scientists, and visionaries are reshaping our cosmic future.

Article originally prepared in Italian for my personal podcast Disruptive Talks (read it here). This content is also available as a Livestream video, here, and in audio podcast, here.

If you’re a Disruptive Talks podcast listener, you know I’ve covered space topics several times. It’s been a childhood passion, well-nurtured by the telescope my grandmother bought me when I was 5 years old. But the origin of this focus goes beyond passion. It stems from reading the interesting World Economic Forum paper on the Space Economy.

This report contains some key data worth highlighting:

- 🚀 The space economy is expected to reach $1.8 trillion by 2035, with an average growth of 9% annually, well above the global GDP growth rate.

- 📈 Five sectors will generate more than 60% of the increase in the space economy by 2035: supply chain and transportation, food and beverages, state-sponsored defense, retail and consumer goods, and digital communications.

- 🌍 Beyond revenue generation, space will play a crucial role in mitigating global challenges, from disaster alerts to climate monitoring, to improved humanitarian response and more widespread prosperity.

- 📡 Data demand will increase by 60% between 2023 and 2035, as consumers and businesses increasingly adopt satellite services in remote areas and for mobility applications.

- 📱 Satellite receivers and chips will become ubiquitous, from smartphones to terminals for connected aircraft and ships. This segment will grow from the current $2 billion per year to $8 billion per year by 2035.

Had you any doubts about whether this market is expanding or of interest? Beyond these numbers, we’ll detail what lies behind this “space economy” and the challenges it presents.

The context: from wars to international collaboration

The historical context of the space economy is characterized by a dynamic evolution spanning from geopolitical tensions to international cooperation.

The story begins with the development of the V-2 rocket during World War II, a project spearheaded by German scientists under Wernher von Braun. This liquid-propellant ballistic missile, capable of reaching altitudes of 88 km, laid the groundwork for future space exploration despite its original military purpose.

In the aftermath of World War II, both the United States and the Soviet Union recognized the potential of this technology. Operation Paperclip, a covert U.S. intelligence program, brought von Braun and over 1,600 German scientists to America, while the Soviets captured V-2 rockets and technical documents. This set the stage for the impending Space Race.

Von Braun’s expertise proved invaluable in the development of the Redstone rocket, which launched Explorer 1, America’s first satellite, in 1958. This 14 kg satellite discovered the Van Allen radiation belts, marking a significant scientific achievement. The same year saw the establishment of NASA, signaling a shift from military applications to civilian space exploration.

The Space Race reached fever pitch with the Soviet launch of Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957. This 58 cm diameter aluminum sphere, weighing a mere 83 kg, orbited Earth for three months, emitting radio pulses detectable worldwide. Beyond showcasing Soviet technological prowess, it raised concerns about potential military applications of space technology, particularly the ability to launch intercontinental ballistic missiles.

The United States responded comprehensively. The Advanced Research Projects Agency (later DARPA) was created in 1958 to advance military technology. The National Defense Education Act was passed to boost science education, addressing the perceived “missile gap.” NASA was established to coordinate civilian space efforts, consolidating existing research bodies into a single, focused agency.

These efforts culminated in the Apollo program. On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to walk on the Moon, fulfilling President Kennedy’s 1961 promise and marking a watershed moment in human history. This achievement, broadcast live to millions worldwide, demonstrated the incredible progress made in just over a decade of focused space exploration.

From competition to collaboration

The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) in July 1975 signaled a profound shift in space exploration dynamics. This joint mission, which saw an Apollo spacecraft dock with a Soyuz spacecraft, symbolized the possibility of international cooperation in space. The mission involved complex technical coordination, including the development of the Androgynous Peripheral Attach System (APAS), a universal docking mechanism that became the standard for future space missions.

The ASTP marked the first international human spaceflight and paved the way for shared scientific experiments and technology demonstrations. It proved that despite political differences, nations could work together in the pursuit of scientific knowledge and space exploration.

This collaborative spirit laid the groundwork for more ambitious international projects, culminating in the International Space Station (ISS). Operational since 2000, the ISS represents the pinnacle of international space cooperation. This orbiting laboratory, involving 15 countries and five space agencies (NASA, Roscosmos, ESA, JAXA, and CSA), circles the Earth at an average altitude of 400 km, traveling at 28,000 km/h and completing an orbit every 92 minutes.

The ISS has been continuously occupied since November 2000, serving as a microgravity and space environment research laboratory. Its modular design allows for ongoing expansion and upgrades, with modules contributed by various participating nations. The station has facilitated groundbreaking research in fields ranging from astrobiology to materials science, providing insights impossible to gain on Earth.

International cooperation in space has expanded beyond low Earth orbit to Mars exploration. The ExoMars program, a joint venture between ESA and Roscosmos, aims to search for signs of past life on Mars. The Mars Sample Return campaign, a collaboration between NASA and ESA, represents one of the most complex robotic space missions ever attempted, designed to return samples from the Martian surface to Earth for detailed analysis.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched on December 25, 2021, exemplifies the latest in space cooperation. This $10 billion project involves NASA, ESA, and the Canadian Space Agency. With its 6.5-meter primary mirror and operation at the L2 Lagrange point, 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, JWST represents a significant leap in our ability to observe the early universe, exoplanets, and other astronomical phenomena. Its infrared capabilities allow it to peer through cosmic dust, revealing previously hidden celestial objects and potentially revolutionizing our understanding of the universe’s origins.

These collaborative efforts not only pool resources and expertise but also foster diplomatic ties, demonstrating the potential of space exploration as a tool for international understanding and peace. As we look to the future, this spirit of cooperation will be crucial in tackling the challenges of deep space exploration, potential asteroid mining, and perhaps even the establishment of human colonies beyond Earth.

The advent of private companies

In recent decades, there has been a paradigm shift with the entry of private actors who have begun to play an increasingly decisive role in the space economy. While government agencies like NASA, Roscosmos, and ESA had long dominated space exploration, a new breed of private companies began to emerge, challenging the status quo and ushering in what’s now known as the “New Space” era.

This transformation can be traced back to the early 2000s when Elon Musk founded SpaceX and Jeff Bezos established Blue Origin. These visionaries, along with others like Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, saw opportunities where traditional aerospace companies and government agencies saw insurmountable challenges. Their entry into the space sector was driven by a combination of technological advancements, changing economic landscapes, and a shared vision of making space more accessible.

The success of these private entities in competing with established national space agencies can be attributed to several key factors:

- Technological innovations: the cornerstone of the private space industry’s success has been its relentless pursuit of innovation. SpaceX’s development of the Falcon 9, the first partially reusable orbital rocket, stands as a testament to this spirit. By successfully landing and reusing the first stage of the rocket, SpaceX dramatically reduced launch costs from about $65 million to $28 million per launch. Blue Origin, with its New Shepard system, focused on suborbital flights and achieved repeated landings of its booster, paving the way for space tourism. Virgin Galactic took a different approach with its air-launched SpaceShipTwo, designed to carry paying customers to the edge of space. These innovations extended beyond launch vehicles. Companies like Planet Labs revolutionized Earth observation with their constellation of small, low-cost satellites, while OneWeb and SpaceX’s Starlink project aimed to provide global broadband coverage using vast satellite networks.

- Investments and funding: The influx of capital into the space sector has been unprecedented. According to Space Capital, investment in space companies reached $8.9 billion in 2020 alone. This surge in funding came from various sources:

- Venture Capital: firms like Bessemer Venture Partners and Lux Capital recognized the potential of space startups, providing crucial early-stage funding.

- Private Wealth: billionaires like Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Richard Branson invested heavily from their personal fortunes.

- Public-Private partnerships: NASA’s Commercial Crew and Commercial Resupply Services programs provided significant contracts to companies like SpaceX and Orbital Sciences (now part of Northrop Grumman).

- Adoption of agile business models: New Space companies adopted lean, agile methodologies traditionally associated with Silicon Valley startups. This approach allowed for rapid prototyping, iterative development, and quick pivots based on market feedback. For instance, Rocket Lab, founded in 2006, developed its Electron rocket in just four years, a fraction of the time typically required for new launch vehicles. The company’s agility allowed it to quickly capture the small satellite launch market, completing 18 successful launches by 2021.

- Expansion of markets and services: private companies didn’t just improve existing services; they created entirely new markets:

- Space tourism: Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin opened up suborbital space travel to private citizens, with tickets selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

- Satellite internet: SpaceX’s Starlink and OneWeb aimed to provide global broadband coverage, potentially revolutionizing internet access in remote areas.

- In-Space manufacturing: Companies like Made In Space demonstrated 3D printing on the ISS, opening possibilities for on-orbit manufacturing.

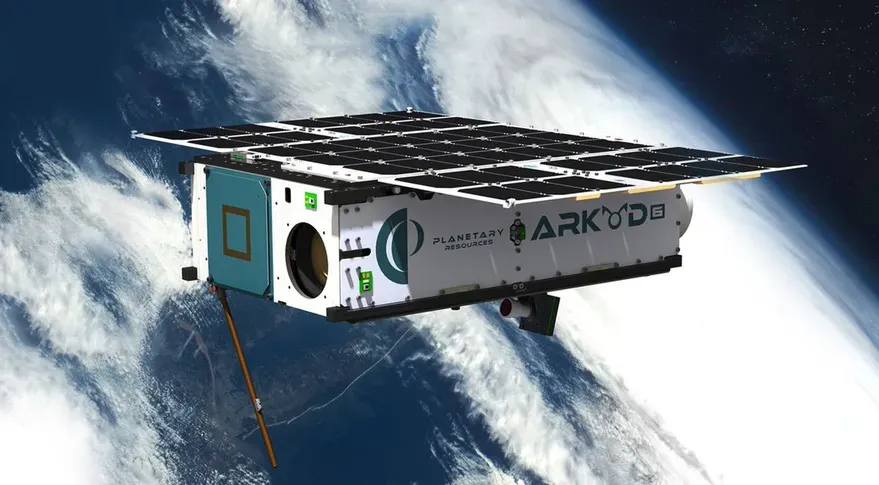

- Asteroid mining: Although still in its infancy, companies like Planetary Resources (now defunct) and Deep Space Industries sparked interest in extraterrestrial resource extraction.

These innovations and market expansions have had a ripple effect throughout the aerospace industry. Traditional giants like Boeing and Lockheed Martin have had to adapt, forming joint ventures like United Launch Alliance to remain competitive in the launch market.

I recommend reading the article “The Strength of Private Players in Space Conquest” by the Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (in italian), which well summarizes how these companies have changed the rules of the game.

The space economy in various sectors

The evolution towards the space economy has materialized through a set of radical transformations in the sector, leading to an epochal change in the way space is accessed and utilized. And, of course, these changes have led to projects that go well beyond the simple launch of satellites or telecommunications projects.

Space Tourism

This sector is emerging as an area of great interest and investment within the space economy, promising to open the doors of space to non-astronauts. Through technological innovation, companies like Virgin Galactic are breaking down the barriers that once made space accessible only to governments and researchers.

Using the SpaceShipTwo vehicle, Virgin Galactic has made significant progress, with test flights demonstrating the feasibility and safety of its operations. As of 2023, it is moving towards offering regular tourist flights, with the aim of making space more accessible to a wider audience.

Security and defense

For several years now, the space economy has played a crucial role in security and defense, through the development of advanced technologies for global surveillance, communication, and monitoring.

For example, Lockheed Martin works closely with government agencies to produce satellites and space technologies that support national and international security. With projects like the GPS III satellite system, which offers improved navigation capabilities and response times, Lockheed Martin is at the center of developing critical infrastructure for defense and intelligence operations.

Mining and resource exploitation

Space resource extraction opens new frontiers for the space economy, promising to provide valuable materials for use on Earth and for future space missions.

In this field, Asteroid Mining Corporation positions itself as a precursor, with the long-term goal of extracting minerals and water from asteroids. This could facilitate access to space resources, supporting human presence in space.

Energy

Space-based energy generation represents a promising field for sustainable development, offering innovative solutions for the growing global energy demand.

Solaren Corp aims to revolutionize the energy sector through the use of solar-capture satellites in orbit, which collect solar energy to transform it into radio waves, then sent to Earth and converted into electricity. This technology promises to provide an inexhaustible source of clean energy, addressing both the climate crisis and global energy demand.

Scientific research

Scientific research also greatly benefits from the opportunities offered by this new economy, allowing advanced studies in fields such as medicine, physics, and environmentalism.

Blue Origin, in addition to its commitment to space tourism, the company founded by Jeff Bezos is deeply involved in scientific missions with the New Shepard launch vehicle. By offering the opportunity to conduct experiments in microgravity conditions, Blue Origin is opening new frontiers for research, allowing universities and research centers to explore unprecedented questions in otherwise inaccessible environments.

You’ve understood it, the space economy is becoming a catalyst for transversal innovation, touching and transforming a variety of sectors through an advanced technological infrastructure and strategic collaborations that push the boundaries of human knowledge and experience.

But why are we talking about the Wild West?

Regulatory framework and challenges

As the private sector becomes a dominant player in space exploration and exploitation, significant challenges emerge. Commercial space entities aim to explore, exploit resources, and even establish infrastructure for tourism in orbit, making a clear international organization of this new market urgent.

Currently, there are some rules governing space activities. The Outer Space Treaty (1967) establishes that outer space cannot be subject to national appropriation, guarantees the freedom of exploration and use of space by all states, and prohibits the placement of weapons of mass destruction in space.

Other significant conventions include:

- The “Rescue Agreement” (1968), which establishes the responsibility of states to assist astronauts in distress and return objects launched into space to the states of origin.

- The “Liability Convention” (1972), which addresses the issue of liability for damage caused by space objects.

- The “Registration Convention” (1975), which requires states to register all launches of space objects.

In the United States, the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (2015) encourages the commercial space sector, facilitating private space commerce through a series of regulations.

At the international level, the United Nations Guidelines for the Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Activities (2018) aim to ensure the long-term sustainability of the space environment.

But most actors and observers of the space economy converge to affirm that these laws and conventions are not sufficient.

Existing international laws do not adequately address the new realities of commercial space exploration, while national laws seek to fill gaps without addressing the set of issues such as space resource ownership and liability for damages, which remain open.

Other challenges related to the Space Economy

As it moves towards new frontiers, this market faces complex challenges that transcend pure legal or technological boundaries.

An emblematic example is the Peregrine Mission One, where Astrobotic‘s plan to bring human ashes to the Moon raised profound questions, encountering opposition from the Navajo Nation for whom the Moon holds sacred significance. This episode underscores how space exploration can intersect with and even contravene deeply rooted cultural and spiritual beliefs, indicating the need for a broader ethical dialogue.

In 2019, the crash of the Israeli Beresheet probe on the Moon introduced the problem of extraterrestrial biological contamination, with the release of dehydrated tardigrades. This raises questions about human impact on pristine celestial ecosystems, drawing attention to the responsibility of preserving the integrity of worlds beyond our own.

Projects such as those of Moon Express and iSpace, which aspire to extract resources such as ice water and rare minerals, highlight the dilemma of appropriation and exploitation of space resources. These activities spark debates on the legality, ethics, and equity in accessing and using space wealth, suggesting that current laws and regulations may not be sufficient to manage emerging space ambitions.

The security and protection of space infrastructures also require attention. The issue of space infrastructure security was highlighted in 2022 when the vulnerability of SpaceX’s Starlink satellites to low-cost hacker attacks was demonstrated. This underscores the critical importance of developing robust systems to protect vital space infrastructures from potentially devastating threats.

I recommend reading the article “The New Space Race” by The Economist to better understand the geopolitical situation of space.

European Consultation on “EU Space Law” and World Economic Forum recommendations

Faced with these challenges, the proactive approach of European institutions, particularly through the consultation on a legislative proposal called EU Space Law, represents a significant step towards regulating the space “Wild West”. The objective of this legislation is threefold:

- Ensure safe satellite traffic, addressing the incremental risks related to space debris and collisions, which threaten the safety of space operations and the sustainability of low Earth orbit;

- Protect space infrastructures against threats such as cyberattacks, ensuring the resilience of critical components on which a growing range of terrestrial services rely;

- Guarantee the long-term sustainability of space operations, promoting practices that enable future generations to access and benefit from space.

The results of the consultation could have a substantial impact, setting standards for safety, sustainability, and responsibility in the use of space. This new regulatory framework could serve as a model for future international agreements, offering a shared path to govern space activities in a fair and sustainable manner.

In addition to this consultation, it will be interesting to see if the recommendations made by the World Economic Forum in its report on the space economy will be followed by various actors.

Leaders of Non-Space Industries

Participate in discussions with the space community: provide demand signals for future use cases and develop potential applications for the next decade (e.g., analyze how space data can be used for industrial applications).

Collaborate and invest with technological innovators: promote the applicability of space in non-space industries by improving the usability and accessibility of space datasets, next-generation communication capabilities, and monitoring and positioning data.

Better integrate satellite and terrestrial systems: collaborate with space actors to ensure continuity of supply chain monitoring, expand service reach in remote areas, and adapt to changes in consumer habits.

Space Industry Leaders

Explore a “space for non-space” approach: invest in marketing and sales for existing or potential use cases across various sectors, demonstrating and customizing analysis products and popularizing technological possibilities.

Consider partnerships with non-space actors: reduce risk in developing new hardware and services and ensure product market fit, such as Earth observation for ground situation assessment and improving precision for autonomous systems.

Co-create protocols and standards: define data formats, security, and hardware interfaces for secure, low-latency, and high-speed communications, and a harmonized and reliable spectrum.

State-Sponsored Leaders

Legislate, standardize, and create policies: create an environment of competitiveness, safety, and sustainability to develop future use cases (e.g., global cooperation on space traffic management and space situational awareness).

Co-invest in space technologies: support industries and the common good by mitigating risks to critical infrastructures and supply chains, providing remote education, telemedicine, and human trafficking prevention.

Build partnerships between state agencies: facilitate knowledge exchange platforms that promote progress on the use of space data and services, organizing cross-sector meetings to inform public resource allocation.

My take

It is crucial to remember that outer space is a common good, not just a frontier for profit.

While commercial ambitions push towards new horizons, it is our collective responsibility to preserve the space environment for future generations. To do this, various entities will need to address the legal and ethical issues that are the natural consequence of increased private space activities.

Beyond these issues, I am among those who see space as an answer to many of the challenges we face on Earth. Contrary to those who criticize investments in space, arguing that we should focus on terrestrial problems, I believe that space exploration is essential for our future.

What do you think? What are your opinions on the advancement of the space economy and the related legal and ethical challenges? How can we promote technological and commercial progress in space while preserving the fundamental principles of equity, sustainability, and international cooperation?

Let me know in the comments!

For further inquiries or assistance with technologies, feel free to reach out.

Notes and further reading

The space economy is a rapidly evolving field with new developments occurring frequently. For the most current information and in-depth analysis, consider exploring the following resources:

- Space Foundation’s “The Space Report”: an annual publication providing comprehensive data and analysis on the global space industry.

- European Space Agency (ESA) – Space Economy: offers insights into ESA’s perspective on the space economy and its impact on European industry.

- NASA’s Reports: detailed analysis and report of NASA’s activities and research.

- Space Capital – Space Investment Quarterly: provides regular updates on investment trends in the space sector.

- The Space Review: A weekly online publication featuring in-depth articles on various aspects of space policy and economics.

- OECD Space Economy: offers policy analysis and data on the space sector’s economic dimensions.

- Satellite Industry Association (SIA) – State of the Satellite Industry Report: annual report providing key statistics and trends in the satellite industry

- United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA): provides information on international space law and policy.

- SpaceNews: a leading source for space industry news and developments.

- Harvard Business Review – Space Industry articles: offers business-focused analysis of trends and opportunities in the space sector.

For academic research and technical papers:

- Journal of Space Policy: peer-reviewed journal covering space policy and economics.

- New Space Journal: focuses on the emerging commercial space industry.